Far from being super heroes the incredible hulks discussed here were places associated with despair and hopelessness.

Over the years that I have been writing for All at Sea, I have avoided getting into trouble by steering a wide course clear of any of the more pungent political issues of the day. If things get harder this month then it is not by design, yet I would have to be the first to admit that there are some undoubted parallels between today and 200 years ago.

One clear difference, though, was back then, Europe was enjoying a new era of international peace and after Trafalgar and then Waterloo the immediate threats on the continent had receded. It was just as well for the ever more dominant Royal Navy, as everything there was in a state of change.

In 1822 the Navy had launched HMS Comet at Deptford, ushering in the era of steam power, and just five years later at Navarino the last battle would take place that would be fought exclusively between sailing ships. Instead, the once proud ships of the line that had been with Nelson at Trafalgar were now moored up in long lines in all of the main naval harbours from Plymouth around to Chatham.

A NEW ROLE

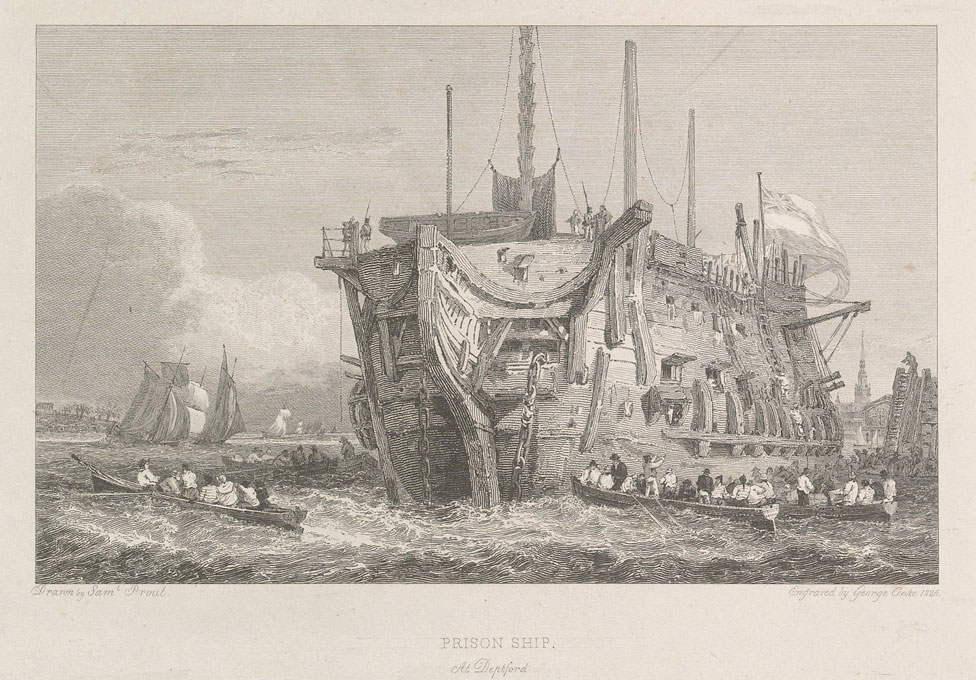

Shorn of their armaments and rigs and with the spaces below stripped out, these once famous fighting ships were employed in a very different role as they were now the dreaded ‘prison hulks’, chock full of prisoners. The UK might have been at peace on the world stage, but affairs at home were a very different matter.

The industrial revolution had brought about huge social change, which was now sweeping equally across the countryside as the first signs of mechanisation started to impact on farming communities. It was not just the civil unrest that worried the authorities, but as events had played out just across the Channel in France some 40 years earlier, the fear of the working population rising up and seizing power was very real indeed.

There were already more than 200 offences that could see a person hung with little in the way of any appeal (at one time the starting point was for theft of anything of greater value than a shilling) and now the number of people being held in jail would be swollen by an influx of what today many would see as ‘political prisoners’. Yet simply hanging people was not only becoming increasingly questionable, but it was also so wasteful when Britain had an almost insatiable appetite for labour resources both at home and in the far-flung colonies.

Much of the expansion work in the Naval Dockyards would be undertaken by prison labour, brought off the ships in the morning and then returned there at night. Conditions on board were dire, with death from disease considered by some as an enviable release, whilst visits from family and friends, an essential part of getting extra rations in the onshore jails, were strictly limited to reduce the risk of escaping.

HULKS ACT

A hundred years earlier the Transportation Act had been signed into Law, which saw so many convicts sent to the USA that the States on the eastern seaboard tried to pass their own laws to prevent any further shipments. A tricky problem became worse with the Hulks Act of 1776, which saw the main naval ports become collection and holding points for prisoners ahead of transportation, with both aspects of the process, the jailing and then the shipping being put out to private enterprise.

Image: Heritage Hunter

The sums quickly stacked up: £32 a year would be paid per prisoner on a hulk, so an old ship, no longer seaworthy for long voyages, holding 300 prisoners was a considerable ‘earner’. The hulks were known as ‘pontons’, which saw many of the hulks sat in mud berths and with several hundred prisoners to a hulk, conditions both on board and around the hull were shockingly insanitary.

Even more disturbing was the fact that the use of hulks to cater for the increase in the prison population was not restricted to just men. Women and small children had their own hulk, the Dunkirk, whilst children older than 11 would be sent to one of the hero ships from Trafalgar, the ex-HMS Euryalus, which was moored at Chatham, a hulk that became a legendary byword for the severity of the regime on board and the atrocious nature of the conditions suffered by the inmates.

The situation became so dire that at one point in the early years of the Victorian era, some 70 per cent of all prisoners were held on hulks, some serving their sentence, others awaiting transportation to the colonies.

Like the hulks, the trade in shipping out convicts was equally lucrative and although a cost per transported prisoner of £5 might not seem much, once delivered to the colonies they could auction off their human cargo to the highest bidder.

A NEW ROUTE

We might not have been shipping African slaves any longer, but for many of the prisoners their rights once transported were severely limited. This trade would come to an end in the late 1770s after the USA gained their independence, only for a new route to open up that could clearly take all of the transportation trade from the UK.

The destination was five to six months sail away in Australia, but whilst some sentences were for life, the majority were for either seven or 14 years. However, the very nature of ‘Transportation’ was clearly intended as a one-way ticket. Escape and return before completion of the sentence was punished by hanging and even those who survived to work their time were still faced with the nearly impossible task of getting back to England unless they could pay or work their way home.

Thankfully the situation would be changing, as public opinion, shocked at some of the horror stories from the hulks and transportation ships, demanded change. More prisons were built ashore and ships en route had to carry a doctor; with better conditions and rations for the prisoners, rate of deaths onboard fell.

The Hulk Act, originally intended as a short-term measure, finally expired in 1857 and just a decade later, the Hougoumont carried the last shipment of convicts to Australia, a process that had seen almost a quarter of a million people shipped around the world.

FLOATING GULAG

Old habits die hard, though, and in the 1920s, following the Bloody Sunday uprising in Ireland, Britain once again resorted to the use of a prison hulk by positioning the old HMS Argenta in Belfast Lough, for the internment of 263 Irish Republican prisoners. Clearly the lessons of the past had not been learnt, as conditions on board the Argenta were described as ‘unbelievable’ with the ship referred to as a ‘floating gulag’. The words below were written about the Argenta, but they could equally have been written at any time in the previous 150 years, the heyday of the hulks.

“When you are on some lonely road, waiting some friends to see,

Let your thoughts turn towards the Argenta,

And sometimes, think of me.”

Solent based dinghy sailor David Henshall is a well known writer and speaker on topics covering the rich heritage of all aspects of leisure boating.

Solent based dinghy sailor David Henshall is a well known writer and speaker on topics covering the rich heritage of all aspects of leisure boating.